|

GOING

BACK TO PLACES THAT I

HAVE NEVER BEEN

Being

a Field Guide to Hanoi and Dien Bien Phu for

Historians,

Wargamers and the More Discerning Type of Tourist

by

Peter

Hunt

Part

Two: Dien Bien Phu

My

own exploration of

Dien Bien Phu

was not

conducted in a completely systematic manner but, for the sake of clarity, we

will not follow my route but divide the battlefield into three areas ~ east

of the river, west of the river and the outlying positions ~ with separate

articles for each.

I

would stress again that these articles are intended more for the buff than

for the casual reader and I’m assuming that you know a bit about the

battle and know what was happening to who, when, where and why.

Thus I shall concentrate on relating the ground to the events and,

hopefully, give you some pointers so that you can best organise your own

trip. If you are not going to

make it to the battlefield sometime soon I hope that anyway I can give you a

few insights that will be useful.

Getting

There and Finding Your Way Around

By

all accounts

Dakotas

were an

unpleasant way to travel, having a disconcerting tendency to drop suddenly

in airpockets over mountains.

Vietnam

being full of

mountains French soldiers tended to prefer the “Toucan”, Junkers 52

Trimotors which were slower, but a lot more stable.

The modern traveller has neither option but it still gladdens take

heart to fly to

Dien Bien Phu

on a plane

with propellers ~ a French built ATR 70.

The

flight from

Hanoi

takes little

more than an hour. Try and get a

window seat in Row D because on the normal approach the view to the East

will give you an instant familiarisation to

Dien Bien Phu

today.

I was sitting in the window seat on the other side.

The planes usually take off and land from the South so, looking West,

the first thing I saw was a “Bison” Chaffee tank sitting on the Huguette

position next to the airstrip I was instantly back in 1954.

After a remarkably easy baggage reclaim I was soon in the car to the

hotel and totally dumbfounded. The

reason is simple. I knew that in

1954 there were 112 houses in

Dien Bien Phu

.

I also knew that in 2002 the population was about 24,000.

My mind hadn’t put the two concepts together.

Instead of the empty valley dominated by hills and the mountains

beyond that I have had in my mind’s eye for the last 30 years I was on a

four lane highway through a major urban development.

Getting my head around this was quite a task and I spent most of my

first afternoon trying to work out which hills were which.

When I flew out I had the view over the town that you would have had

from Row D on the way in. The

hills stand out as elevated, undeveloped islands in the sea of urban sprawl

and this aerial familiarisation is a lot clearer and easier than working

things out at ground level.

Although

you can get guide pamphlets to

Dien Bien Phu

’s

attractions I couldn’t get a decent street map of the place.

Beware, the map in “Lonely Planet” was apparently drawn by

someone who was both directionally, and dimensionally challenged and who was

just passing through anyway. To

try and put things in better context please have a look at these two maps of

Dien Bien Phu

in 1954 and

today.

.

Taking

my lead from the “Lonely Planet” I stayed in the Muong Than Hotel which

they said was the best hotel in town. It’s

a bit far out, closer to Beatrice than to Dominique, but it has very helpful

staff and provides reasonably clean, two star comfort, with hot water,

aircon, telly and sit down toilets. There

is a swimming pool, billiard room, bar of sorts, massage establishment and

restaurant that includes mountain mouse, chow meat, porcupine meat, sanbar

deer and wild boar on its menu so you needn’t starve.

“Lonely Planet’s” second choice is the Dien Bien Phu Hotel

which is more centrally located but doesn’t look as nice as the Muong

Than, although I wasn’t able to check out the rooms.

Getting

around you have the same options open to you as in

Hanoi

except that

taxis only operate from the main hotels.

The inner valley positions are all within walking distance (although

it can be hot, so drink lots of water, which you can buy everywhere,) or you

can hop a motorbike between spots. To explore further afield you will need

to hire a motor bike, ($20 US a day, bargainable,) or an air-conditioned

taxi ($50 US a day,) I chose the latter, didn’t haggle and had a splendid

time.

To

find things I used the maps in Bernard Fall’s “Hell in a Very Small

Place”, individual maps of the strong points downloaded from the “Dien

Bien Phu Infos” website

and the 1:250,000 sheet map “Dien Bien Phu” that you can buy for $3 US a

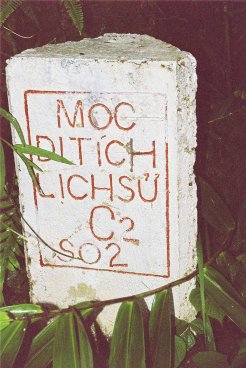

sheet in Hanoi. The battlefield is well marked. There are large

“monument” style markers and permanent maps at many of the major points,

and practically all the sites are marked by smaller “milestone” type

markers. Whilst the larger

markers include a text explanation (in Vietnamese of course,) that often

identify the position using the French codename, most of the markers use the

Viet Minh designation. Also Viet Minh units are usually described by their

title rather than by their regimental number as used in western sources.

This can be a little disconcerting so I will shortly add an annex to this

article giving “translations” of French and Viet Minh designations.

Finally, if you need to orient yourself as I did the easiest way is

to find the Bailey Bridge and take compass bearings on the hills.

The bearings will also given in the Annex.

.

Milestone Battle

Marker

The

flight from

Hanoi

arrives and

leaves in early afternoon so I spent an afternoon, a morning and a whole day

on the interior positions; and another day trip to visit the outlying

positions. This was adequate but

another full day for the interior positions would have been nice.

I was relatively lucky with the weather but unless you are visiting

in the dry season (November to March,) an extra day will also give you some

flexibility in case of a not unlikely downpour or an airplane delay.

So although I spent three nights in

Dien Bien Phu

I would

recommend four. After all I live

near enough and fully intend to go back, you may not have that luxury.

Armed

with your maps, compass, stout boots, (for hill climbing and paddy bashing,)

long trousers and long sleeved shirt, (for mossies and moving through the

undergrowth,) insect repellent, camera and water you are now ready for your

exploration of Dien Bien Phu.

East

Of The River

The

Dien Bien Phu

Museum

The

obvious place to start is the Museum. This

is open from

8:30 a.m.

to

4:30 p.m.

with a siesta

from about

11:00 a.m.

to about

2:00 p.m.

You buy tickets for the Museum and the Eliane position from the

little shop just outside the entrance to the Museum.

This shop also sells bits of “genuine” parachute silk (at $2 US I

thought it was worth a punt, maybe it really is genuine,) and some

battlefield relics, mostly rusted personal items.

A real bargain in this shop are commemorative badges and stamps.

The stamps go for 5000 Dong each so a full set costs about $2 US.

On EBay these sets go for between $10 and $30 US.

The

museum consists of one large, (very badly lit,) exhibition hall, two outside

display areas, one for French kit, one for Viet Minh; and a separate

exhibition hall dedicated to the T’ai people of the area.

The

main hall has lots of interesting pieces.

My favourites were General De Castries’ bath, (a real metal one, I

don’t know if it was flown in or salvaged from the old Governor’s House

on Eliane,) a Japanese 75 mm Meiji 41 Regimental gun with its distinctive

tubular trail used by the Viet Minh, (Raventhorpe do a nice model of

these),

one of the 6 barrelled Katyusha rocket launchers used in the final stages of

the battle and the contents of a “Lazy Dog” Bomb, the precursor of

today’s sub-munition weapons. Also

worthy of note are a manikin of a typical Viet Minh soldier at

Dien Bien Phu, wearing a

cape of camouflaged parachute silk; and a fanion of a Foreign Legion Unit.

The hall also contains a smaller version of the battle diorama that

is in the

Museum.

The

Viet Minh weapons outside are probably not from the battle.

After all the 351st Heavy Division was not in the business

of setting up Museums and when they left they took their 105 mm howitzers

and 37 mm AA guns with them. There

was still a war to fight. But

for all that the weapons in the museum are good examples of the sort of

equipment the Viet Minh used.

On

the other hand there can be little doubt about the French weapons outside.

There is an 8” Howitzer (one of four originally in the valley,) in

relatively good condition. A

“Bison” Chaffee tank in quite good state, along with two more tank

wrecks, and the rusting wreckage of six GMCs, six jeeps, a Dodge 1½ tonner

and a Dodge weapons carrier.

Pay

particular attention to the serial details engraved on the tube of the 8”

howitzer. This barrel was made

at the WVT Arsenal (tube number 14459) in 1954 ~ i.e. it was brand new at

the battle. Along with the 37 mm

Flak used by the Viet Minh this is a good example of the proxy aid given by

both superpowers to the protagonists in Indochina

.

The Main

Cemetery

Directly

across the road from the Museum is the main cemetery.

Cemeteries are supposed to be sobering places, and because of their

symmetry military cemeteries are even more so.

This one is no exception to this rule and here lie the Viet Minh

heroes of the battle, in serried ranks even in death.

The cemetery is not the largest on the battlefield, the two on either

side of Gabrielle way to the north are bigger, but because of its location

this cemetery is the focus of the Vietnamese commemoration of their dead.

Main Cemetery - outside

wall

The

decorative garden between the road and the cemetery is not well maintained.

Buffalo

roam through

what should be lawns and pools. But

the cemetery itself is well looked after.

Built like a medieval fortress, complete with a moat and ornamental

gateway, the outer wall is covered with mouldings and frescos showing the

events of the battle ~ a sort of pictorial history.

It is the inner wall that is more sobering however – cloistered and

cool even in the heat and humidity of the day this is the Vietnamese version

of the American “wall” on the Mall in

Washington

.

It contains the names of the Viet Minh fighters who fell at the

battle. Just like its Washington

counterpart

you see people looking for the names of their comrades and relatives and

votive offerings are left for them.

As

well as a place to reflect upon the cost of war and the sacrifices for

liberation, the cemetery had three special points that struck me.

Firstly, in a special plot on the northern side, is the grave of Phan

Dinh Giot, the first Viet Minh hero of the siege who fell in the assault on

Beatrice.

Secondly

there is the focus of the cemetery at the eastern end which consists of an

altar flanked by two larger-than-life sculptures of Viet Minh fighters.

These are carved in a rugged “socialist realism” style and depict

assault troops again wearing the distinctive parachute silk capes of the

battle. The sculptures are

covered in fading gilt paint, that looks a bit shabby close up, but when the

afternoon sun catches the stone and the gilt the effect is quite dramatic.

|

|

|

The Viet Minh fighters |

E2 and Tank Bazailles

look down on the cemetery |

The

third dramatic thing about the place is simply the view of Eliane 2 just

across the road to the north. Although

the lowest of the “Five Hills” E2 was one of the most hard fought over

and from the cemetery it is easy to see why.

The hill itself dominates the low ground on which the cemetery stands

and its flanks rise like a near vertical wall to the cemetery.

It is a very fitting backdrop to the last resting place of the men

who fell on it.

Eliane

2

Eliane

2 is the best preserved of all the hill positions.

It is the main site commemorating the battle from the Vietnamese

point of view and the hill also has deep significance for the French.

This is because of the nature of the battle for the hill itself.

On most of the other positions the battles consisted of ferocious

Viet Minh assaults which either overwhelmed the position after horrendous

losses or were repulsed with horrendous losses.

If a position was taken the French would either retake it with a

counterattack, only to lose it later to another Viet Minh attack; or the

position would be given up completely. Eliane

2 was a different situation. The

initial Viet-Minh assault stalled on the top of the hill and the French,

realising that if the hill fell all of

Dien Bien Phu

would fall,

determined to pay any price to hold on.

As a result the battle for Eliane 2 came to resemble more the trench

warfare in World War I or the “meat grinder” operations of Korea than

the normal pattern of warfare in Vietnam in general or Dien Bien Phu in

particular. Thus the French and

the Vietnamese were locked in combat on Eliane 2 for 38 days.

Unable to go over the top of the hill the Viets eventually went under

it, digging a mine and filling it with explosives salvaged from a shot down

French bomber. When the mine was

exploded and the hill finally taken on

6th May, 1954

Dien Bien Phu

had only one day to live.

The

entrance to E2 is paved and well signposted off the main road.

The top of the hill is fenced off and you have to pay to get in at

the museum ticket office. However,

the rest of the hill is open to all. Before

you climb the hill however, note two things at the bottom.

The first is a bunker right next to the junction of the hill road and

the main road which the Vietnamese called “Manikin Knoll” because of the

shape of the decapitated tree on it. This

bunker does not feature significantly in French or English language accounts

of the battle but “The capture of Hill A1” in Vietnamese Studies No. 3

points out that it was decisive because the initial attack on the hill on

30th March, 1954

included a flanking move to the south of the hill to cut it off.

This stalled because of fire from the bunker.

Because the Manikin Knoll held, the French still had a route to feed

reinforcements up the hill. Because

they could do that the hill held. Because

the hill held Dien Bien Phu

held.

The

other thing to look for here is the large descriptive plaque by the road.

Like the other plaques on the battlefield it includes the details of

the action and the Viet Minh units involved and is decorated by the badges

of the French units involved. Nothing

odd about this but if you look closely at this plaque you will see that it

includes the badge of the main non-communist Vietnamese unit in the battle

the 5th, Vietnamese Parachute Battalion (5 BPVN) which was known

as the “Bavouan,” and which fought as well any French or colonial unit

during the battle. I was

strangely pleased by this little sign that, although during the war the

nationalist Vietnamese units were disparaged as “puppet troops”, when it

came to commemorating the battle the Vietnamese recognised their erstwhile

enemy compatriots as worthy opponents.

.

Viet Minh

Memorial on E2

As

you enter the enclosure on the top of the hill the first thing you see is a

marble monument commemorating the battle, behind which are the remains of

the cellar of the old French Governor’s House.

Although when the French occupied the valley they demolished the

house for building materials, they fortified the cellar.

It was this masonry cellar, held by a few Moroccan tirailleurs, which

stalled the Viet Minh initial attack on the top of E2.

Careful reading of “The Capture of Hill A1” reveals that this was

because of a rare failure in Viet Minh battlefield reconnaissance.

Although the Viet Minh must known that this was the site of the

Governor’s House they did not put two and two together regarding the

underground masonry defences and the assault units did not have effective

enough demolition charges to deal with them.

The

trench works around the summit have been cemented to save them from erosion

so they are a lot tidier than they would have been in the siege but,

presumably, the shape and depth of the trenches is a fair representation.

To the south of the summit tank “Bazailles” looks out broodily

over the cemetery. The tank was

immobilised during a French counter attack on the hill and was then used as

a machine gun nest for the rest of the siege.

.

Tank

Bazailles in the rain

From

the eastern fence of the summit enclosure you get a perfect view down the

glacis of the hill, an open slope that the French called the “Champs

Elysee” and up which the Viet Minh assaults had to charge through the

French fire. Beyond you can see

“Phoney

Mountain” and “Bald

Mountain”, two hills

which the French did not occupy and which the Viets used as their base of

fire. Where the road now runs

(incidentally to the best restaurant in Dien Bien Phu), between E2

and the two hills, used to run the gully in which the Viet Minh prepared

their attacks. As such it was

the obvious target for French artillery and Vietnamese soldiers were cut

down in their hundreds here. All

the side streets in

Dien Bien Phu

are unlit and

I walked down this particular road on a moonless night during the “hungry

ghost” festival when a few old ladies were burning offerings to appease

the restless souls of the dead. I’m

not a nervous person but it was still very spooky!

Because he relied on the use of the gully and failed to prepare

approach trenches through this killing zone the Viet Minh commander of the

initial assault was held responsible for the failure and “removed.”

Before

you leave the summit look to the north and you can see most of the “Five

Hills” on which the defence of

Dien Bien Phu

rested, and

how they relate to each other. The

tallest is Dominique 2, now crowned by its tower which appears to dominate

the whole battlefield. In

between Dominique 2 and E2 you can see the mass of Eliane 1 and 4.

Look carefully and you will see that although D2 is much higher than

the Elianes there is enough dead ground on E1 and 4 to protect most of them

from fire from D2, and these two hills partially protect E2 from D2.

Thus, although the French lost D2 the Elianes were still, barely,

tenable. However if E2 were to

fall, flanking fire from it would make E1 and E4 untenable and vice-versa.

Thus the French were able to hold on by their fingernails until

almost the end.

You

leave the summit by the way you came up and follow the fence around the

south side. This brings you back

to the Champs Elysee and the mine crater, which has been cemented to stop

erosion. You can then walk down

the hill where there is a plaque to mark the entrance to the mine tunnel and

a re-creation of the approach sap from the gully (now road) to the mine.

This walk will leave you with a good idea why the battle for E2 went

as it did. It was formed by the

shape of the hill itself, which is rather like a door wedge.

The North, South and West slopes are steep, and the summit is near

the West, French, end. However,

the Eastern approach is relatively gentle.

Thus the Viet Minh assaults were channelled into this killing zone

which was covered by direct French fire from the summit and E4; and by

zeroed in artillery both from the main position and from Isabelle to the

south. That E2 was held so long,

and eventually taken, is a tribute to the determination of the soldiers on

both sides of this battle.

|

|

|

The

"Champs Elysee" looking down from the French position

over

the mine crater to "Old Baldy" |

Elianes

1 and 4

E1

and 4 are two hills joined by a low saddle.

E1 fell to the Viet Minh on the first day of their assault on the

“Five Hills” on March 30th. Realising that the hill was vital the French counter-attached and

retook it but, like on D2, they had to withdraw because, due to Cogny’s

lack of action during his “Night at the Opera,” there were no

reinforcements to allow the French to hold onto the ground that they had

retaken at such cost. However,

the French soon came to realise that E4 could not be held without E1 and so,

on April 10th, they launched a counterattack and retook it.

The Viet Minh however were just as aware of E1’s importance and,

under a withering bombardment, they launched their own counterattack and

took half the hill. The French

threw in their last reserves ~ companies from French, Foreign Legion and

Vietnamese paratroop battalions.

In

my favourite part of one of my very favourite books, “Hell in a Very Small

Place”, Bernard

Fall describes what happened next:

“Then

something very strange happened. Something

which, in the recollection of the thousands of men who heard it that night,

had rarely happened before in

Indochina

. As the hundred

Legionnaires and French paratroopers stormed across the low saddle between

E4 and E1, they began to sing.”

The

French and the Legionnaires had marching songs going back to their founding.

But the Vietnamese paratroopers of the Bavouan had:

“[no

such]… rousing marching song that could be shouted at the top of one’s

lungs if only to drive out one’s fright.

But there was one song which was then still in the cultural inventory

of every Vietnamese schoolboy, and that was the French National Anthem, the

Marseillaise. As the Vietnamese

paratroopers in turn emerged on the fire-beaten saddle between the hills

there suddenly arose, for the first and last time in the

Indochina

War, the Marseillaise. It

was sung in the way it had been written to be sung in the days of the French

Revolution, as a battle hymn of the

French

Republic

. It was sung

that night on the blood stained slopes of Hill Eliane 1 by Vietnamese

fighting other Vietnamese in the last battle France

fought as an Asian Power.”

This

account sends little tingles up my spine every time that I read it.

So it was very important to me to find the saddle between E1 and E4.

This turned out to be so easy that I didn’t believe it and had to

go back twice to convince myself I was in the right place!

Sadly

the Western face of E1 has already been cut back for building work but E4 is

untouched. Oddly enough this is

a disadvantage because although there appears to be a path to the top of E4

it is completely overgrown and I could only get about half way up.

You might have better luck in the dry season when the ground cover

and bushes will not be as thick. Even

so the bushes are above head height so I don’t think that you will see

much from the top.

.

The "Saddle" today

The

“saddle” is in fact the road between the two hills.

The reason that I didn’t believe it was because it is hardly a

saddle at all. In my minds eye I

had pictures of the paras climbing a high steep slope.

Although the sides of the hills are quite steep, probably more so now

than in 1954, neither hill is particularly high and the “saddle” is only

a few metres above the level of the plain below.

There is a path to the top of E1 but this has been cut off by the

slope works and the other approaches are overgrown like E4.

As you proceed down the road ~

Giot Street

~ which

actually encircles the South, East and North faces of E1 you can get a good

feel for the lie of the land. The

flanks of E1 are quite steep and there is enough dead ground to protect it

from D2. However from both E1

and E4 the side of D2 is open. That

is why the three hills were so interdependent.

Dominique

2

Dominique

5, the linking position between D2 and E1/E4 has disappeared under

development, but you can’t miss D2. It

is by far the highest hill in the central position at 550 meters and it is

now crowned by a radio mast. A

paved road leads to the top, a steep but not difficult walk, but then I was

not wading through mud with a combat pack and rifle, and no one was shooting

at me either. The road follows

the South flank of the hill so you get good views of E1, E2 and E4 and then

curves around the eastern and northern sides at the peak.

This gives you views out to Beatrice and, providing its not raining,

you should be able to pick out the monument on the top of that hill which

will bring home to you its relative isolation.

But

what about the view to the West? From

the top of D2 you would get a splendid view of the whole of

Dien Bien Phu

position.

I say “would” because the top of the hill is taken up by a

telecommunications centre of which the mast is the most obvious part.

Like all such facilities in

Vietnam

it is closely

guarded and off limits to tourists. The

area outside this facility is heavily wooded so most of the western views

are blocked.

Once

you get over this disappointment the things that strike you are D2’s

height and steepness. The

Western and Southern faces, (i.e. those facing the Viet Minh,) are the

steepest. The present road runs

anti-clock wise around the hill from the “6 o’clock” position until it reaches the summit at the “11 o’clock” position. In 1954 there

was a path going direct to the summit from the “9 o’clock

position”

and a jeep track from Route 41 reaching the summit and the “11 o’clock” position. Since these two

routes were more or less direct they must have been much steeper than the

present road.

Thus

the Viet Minh had the hardest approaches and did well to take the hill in

their March 30th attack, even though its defenders wore some of

the least determined units in the garrison.

The French did equally well to retake it, but it is a very big hill

in

Dien Bien Phu

terms and

would probably require the best part of a battalion to hold it.

Here its very steepness was a disadvantage because there was so much

dead ground that would require a lot of troops to properly cover the

approaches with fire, especially after D1 and E1 on its flanks had fallen.

But if the French had had the reinforcements to do this I can see no

reason why D2 should not have held out like E2.

No doubt the Viet Minh would have continued their assaults as they

did on E2. No doubt the

bloodletting would have been horrendous.

But, since Viet Minh morale was close to cracking at the end of the Battle

of the Five

Hills, another meat grinder on D2 might have been enough to tip the balance.

Also the morale effect on the French garrison would have been

significant. D2 is really the

only hill that can be clearly picked out from anywhere in the French lines.

With D2 in Viet Minh hands the whole of the French central position

was under direct observation and much of it within sniper range.

Had it been held it would have offered protection to some of the main

position and would also have served as a visible, and potent, symbol of

French defiance. However, this

is just a “what if”.

The

French didn’t have the reinforcements.

They were sitting on an airfield in Hanoi awaiting Cogny’s order.

Thus, having retaken the hill the French were forced to give it up

again. The Paratroop

reinforcements that could have dropped on 30th/31st March were eventually fed in on April

1st to 4th.

Too little, too late.

Dominique

1

D1

was the northern anchor of the Five Hills being located between Route 41 and

the river. It was a poor

position to hold, exposed to Viet Minh fire on two sides with lots of

undergrowth nearby to give the enemy cover.

It is really just the westernmost, and lowest, eminence of a series

of hills running from the river all the way to Beatrice, the most easterly

of all the French positions. Once

Beatrice fell D1 was very vulnerable. Although

its southern face could be protected from D2 the same Viet Minh juggernaut

that overran the larger hill made short work of D1.

Much

has changed at D1 today. It is

now sandwiched between Dien Bien Phu’s main market and a road.

It is marked by the usual “milestone” markers but both the faces

of the hill have been cut back for development and the road and the top is

overgrown. Having clambered up

the embankment by the marker I was unable to find a path to the top.

Perhaps you will have better luck at the end of the dry season.

The “Non-Hill”

Positions

The

remaining positions east of the River, E3, E10; and D3, D5 and D6 have

disappeared under developments. I

could find no markers for these. But,

as you walk towards the Bailey Bridge on your left you will see Dien Bien

Phu’s other, more colourful, market and on your right, in a small bog, you

will see a large monument type marker. This

marks the site of Piroth’s bunker at E12.

From

the French perspective

Dien Bien Phu

is a tragedy

and in it Piroth is probably the most tragic character.

A one armed artillery veteran he was supremely confident of his

gunners’ ability to beat off any Viet Minh attacks.

However the overwhelming artillery superiority that the Viet Minh

demonstrated at the beginning of the battle neutralised his guns and

destroyed most hope for the garrison; and with it Piroth’s personal and

professional pride too. Piroth

was a man of honour and took full responsibility for his misjudgement on the

most direct way. Unable to cock

a pistol because he had only one hand, he held a grenade to his chest and

committed suicide in his bunk.

|

|

"Piroth's

Memorial" disconsolate in its bog |

Although

much of the view is blocked by buildings if you look North – East from

this site you are looking over the ground where the Senegalise gunners of Lt

Brunbrouck’s battery of the 4th Colonial Artillery fired over

open sights at the victorious Viet Minh descending from D1 and D2 on that

first night of the Battle of the Five Hills.

Had they reached the river and the bridges all of the later struggles

for the hills would have been irrelevant.

Dien Bien Phu would have fallen five weeks earlier than it did. But

Brunbrouck’s vollies stopped the assault that night.

I hope that it was some consolation to the Shade of Piroth that it

was the artillery that saved Dien Bien Phu.

Unlike

the Viet Minh you can cross the Bailey Bridge and explore the positions West

of the river in the next part of this article.

go to part one

back to

vietnam go

to part three

|