|

Die Schlacht Von

Bullenkopf

an

after action report of the game held 17th - 18th

November 2001

by

Peter Hunt

The History

In

an alternative 1813 Archduke Charles of

Austria

came out of retirement to lead the struggle against

Napoleon. The French Army of

Germany was well dispersed but Napoleon kept under his personal command the

Infantry of the Imperial Guard, a Reserve Cavalry corps, a line infantry

corps of Poles and Frenchmen and the Saxon contingent with a division each

of horse and foot. Just as at

Lautzen and

Bautzen

the Emperor was hampered by his lack of scouting cavalry

and so it was to the surprise of all concerned that Napoleon and Charles

blundered into each other in a meeting engagement on the rolling Saxon

countryside near the small town of

Bullenkopf. Charles’ forces were of a similar size to the

Emperor’s: an Austrian corps of three divisions, a Prussian corps of two

divisions, a reserve cavalry division and an under strength grenadier

division.

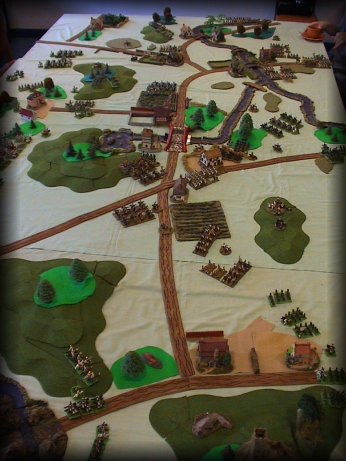

The

terrain was unremarkable. Over a

space of three miles by one and a half miles a series of gentle, often

wooded, hills broke the field into four main areas. From

the French right two wooded hills gave way to a wide valley on the other

side of which was a series of hills, woods, ponds and villages that made up

the centre of the position. The

left was dominated by a stream about a mile from the French positions with

woods, hills and villages on both banks. The

terrain was unremarkable. Over a

space of three miles by one and a half miles a series of gentle, often

wooded, hills broke the field into four main areas. From

the French right two wooded hills gave way to a wide valley on the other

side of which was a series of hills, woods, ponds and villages that made up

the centre of the position. The

left was dominated by a stream about a mile from the French positions with

woods, hills and villages on both banks.

From

6AM

both sides started warily deploying into the battle

area. Both Napoleon and Charles

were concerned about their flanks and kept almost a quarter of their forces

deployed outside the battlefield to prevent the other outflanking them. The

two played a cat and mouse game of bluff and counterbluff trying to get

territorial advantage without committing themselves outright. Then,

just before

9AM

, Napoleon quickly pulled in his Reserve Cavalry, which

had been outside the field protecting his flanks, and massed them in his

centre. Thus, at one stroke, the

Emperor had achieved numerical superiority on the field and the battle was

on.

The

Emperor had positioned the Poles on his right flank with the French

infantry, and dragoons of the Reserve Cavalry covering the valley. Opposite

them were one Prussian division and the Austrian Reserve Cavalry.

Half of the Saxon foot made up the French centre with the French

elite heavy cavalry behind them. Then

came the Imperial Guard. One Austrian and one Prussian division faced this

sector. The remainder of the

Saxon infantry and the Saxon horse covered the French left, faced by one

Austrian division and a brigade from one of the Austrian divisions further

out on the flank, off the battlefield. Neither

side’s deployments were perfect. The French infantry on the right was

stretched out very thinly over a mile and a half, and half of the Saxons

were separated from their main body. On

the Allied side although their divisions were well concentrated the corps

were intermingled and the individual divisions were too far apart for the

corps commanders to coordinate their actions. The

Emperor had positioned the Poles on his right flank with the French

infantry, and dragoons of the Reserve Cavalry covering the valley. Opposite

them were one Prussian division and the Austrian Reserve Cavalry.

Half of the Saxon foot made up the French centre with the French

elite heavy cavalry behind them. Then

came the Imperial Guard. One Austrian and one Prussian division faced this

sector. The remainder of the

Saxon infantry and the Saxon horse covered the French left, faced by one

Austrian division and a brigade from one of the Austrian divisions further

out on the flank, off the battlefield. Neither

side’s deployments were perfect. The French infantry on the right was

stretched out very thinly over a mile and a half, and half of the Saxons

were separated from their main body. On

the Allied side although their divisions were well concentrated the corps

were intermingled and the individual divisions were too far apart for the

corps commanders to coordinate their actions.

The

commanders’ briefings for the coming battle were both instructive, and set

the tone for what was to come. Napoleon,

having pulled the Reserve Cavalry off his left flank to give him superiority

in the centre succumbed to his fears of a flank attack again and ordered the

best part of them, the heavies, back to that flank to support the Saxons. He

did however order the separated part of the Saxon foot to rejoin their

colleagues and these, with the Imperial Guard, would allow him to attack

through Bullenkopf. The French

and Polish line infantry, supported by the dragoon division was expected to

hold the wooded heights on both sides of the valley and the right flank

beyond. The good part of this

plan was that the Emperor had sorted out all of his corps so that they could

fight together as cohesive units. The

bad part was that the Reserve Cavalry would be wasted for most of the battle

whilst the line infantry on the right was perilously weak for the task

allotted to it. The

commanders’ briefings for the coming battle were both instructive, and set

the tone for what was to come. Napoleon,

having pulled the Reserve Cavalry off his left flank to give him superiority

in the centre succumbed to his fears of a flank attack again and ordered the

best part of them, the heavies, back to that flank to support the Saxons. He

did however order the separated part of the Saxon foot to rejoin their

colleagues and these, with the Imperial Guard, would allow him to attack

through Bullenkopf. The French

and Polish line infantry, supported by the dragoon division was expected to

hold the wooded heights on both sides of the valley and the right flank

beyond. The good part of this

plan was that the Emperor had sorted out all of his corps so that they could

fight together as cohesive units. The

bad part was that the Reserve Cavalry would be wasted for most of the battle

whilst the line infantry on the right was perilously weak for the task

allotted to it.

“On

the other side of the hill” Charles immediately withdrew the units off the

battlefield to his right: the grenadier division and two-thirds of another

infantry division, and pulled them back behind his centre, still concealed

but able to intervene at short notice. Since

Napoleon was to commit his best cavalry to meet a non-existent threat from

these troops it is clear that the Archduke had pulled off a successful

tactical deception. The question

was could he capitalise on it? His plan was to put pressure on the French

right and centre until something cracked and then exploit with the off field

forces. The only problem with

this was that nothing was done to sort out the intermingling and stretching

out of the corps. As a result

the individual divisions would fight largely separate battles instead of

delivering coordinated and sustained blows against the French. “On

the other side of the hill” Charles immediately withdrew the units off the

battlefield to his right: the grenadier division and two-thirds of another

infantry division, and pulled them back behind his centre, still concealed

but able to intervene at short notice. Since

Napoleon was to commit his best cavalry to meet a non-existent threat from

these troops it is clear that the Archduke had pulled off a successful

tactical deception. The question

was could he capitalise on it? His plan was to put pressure on the French

right and centre until something cracked and then exploit with the off field

forces. The only problem with

this was that nothing was done to sort out the intermingling and stretching

out of the corps. As a result

the individual divisions would fight largely separate battles instead of

delivering coordinated and sustained blows against the French.

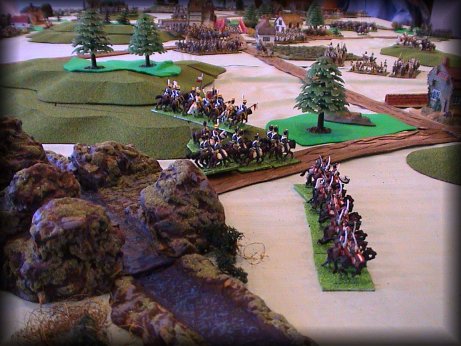

The

battle opened with a cavalry clash in the central valley. To

give himself room to manoeuvre the Emperor sent forward a dragoon brigade. This

was to have been met by four regiments of Austrian light cavalry. But,

it being too early in the morning and not having had their schnapps yet,

half of these refused to charge and their comrades who did charge were very

roughly handled, with the French dragoons breaking through to ride down some

of the Austrian infantry coming up behind. The

remainder of the Austrian light horse woke up and a regiment of cuirassiers

was committed to stabilize the situation. The

French threw in the second brigade of the dragoon division and by

10AM

the honours were roughly equal. The

Austrian cavalry had received a bloody nose, and its pride was certainly

hurt, but the regiments had not suffered major damage. French losses had

been similar to the Austrians but with smaller, less robust regiments they

felt the effects more. As the

dust cleared however it was clear that the leadership on both sides had been

in the finest tradition of the cavalry: and that they had paid the ultimate

price with one French and two Austrian brigadiers dead. Since

both the Austrians were from the Reserve Cavalry division, that unit, which

should have been the Allies’ main striking force, suffered from sluggish

command for the rest of the battle.

On

the French far right their only light cavalry brigade was probing forward

across a stream towards the wooded heights that formed the side of the

central valley. Here the leading

regiment of Polish lancers came face to face with the last uncommitted

Austrian cavalry unit: more cuirassiers! The

Emperor had made it clear that he expected the Poles to charge. The

odds of taking out the cuirassiers were indeed long, but if it could be done

then the way to the Austrian rear was open. The

Polish commander assessed the task given him, no doubt he thought back to

the

Pass

of

Somosierra

where, in 1808, Napoleon had sacrificed another Polish

light horse regiment for no gain. The

Emperor had been wrong then, maybe this time he was right. In

circumstances like these there was only one thing for a Pole to do. He

shrugged his shoulders, then straightened his back, drew his sabre and

shouted charge over his shoulder… Twenty minutes later the Poles and

another chasseur regiment of the brigade were back over the French side of

the stream, broken, blown and vowing never again to let a Corsican

artilleryman tell Polish lancers how to do their business. Much

chastened the light cavalry withdrew behind their infantry to regroup, minus

the chasseurs who arrived at

Leipzig

three hours later claiming that they were the only

survivors of the Emperor’s defeat! On

the French far right their only light cavalry brigade was probing forward

across a stream towards the wooded heights that formed the side of the

central valley. Here the leading

regiment of Polish lancers came face to face with the last uncommitted

Austrian cavalry unit: more cuirassiers! The

Emperor had made it clear that he expected the Poles to charge. The

odds of taking out the cuirassiers were indeed long, but if it could be done

then the way to the Austrian rear was open. The

Polish commander assessed the task given him, no doubt he thought back to

the

Pass

of

Somosierra

where, in 1808, Napoleon had sacrificed another Polish

light horse regiment for no gain. The

Emperor had been wrong then, maybe this time he was right. In

circumstances like these there was only one thing for a Pole to do. He

shrugged his shoulders, then straightened his back, drew his sabre and

shouted charge over his shoulder… Twenty minutes later the Poles and

another chasseur regiment of the brigade were back over the French side of

the stream, broken, blown and vowing never again to let a Corsican

artilleryman tell Polish lancers how to do their business. Much

chastened the light cavalry withdrew behind their infantry to regroup, minus

the chasseurs who arrived at

Leipzig

three hours later claiming that they were the only

survivors of the Emperor’s defeat!

Meanwhile

Charles had thrown a whole division into the wooded heights on the other

side of the valley next to Bullenkopf. This

allowed the Austrians to position artillery on both sides of the valley into

which the French dragoon division again came forward. The

Emperor expected the Polish infantry to support the dragoons on their right

but since the Poles were already facing an equal number of Prussians, with

more arriving on the flank, this was quite unrealistic. As

a result the dragoons were caught in crossfire facing a solid line of

Austrian horse. One dragoon

regiment was destroyed and the others withdrew behind the French centre to

lick their wounds.

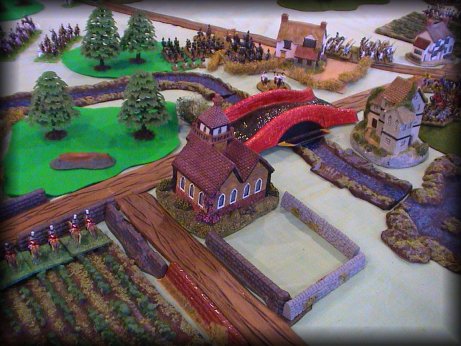

At

Bullenkopf the Imperial Guard and the Saxons came forward to be met by the

second Prussian division in close fighting amongst the villages and woods

where both sides gave as good as they got. The

French positioned “The Emperor’s beautiful daughters”, the 12 pounders

of the Guard Artillery, on the open hill to the left to dominate a swath of

the battlefield. The gunners

amused themselves by demolishing any enemy batteries that deployed in range

and flattening some of the Prussian occupied buildings. But

although the 12 pounders’ firepower was dangerous their major effect was

to create a vacuum swept by fire to the left of the Prussians that extended

all of the way to the Allied right where the Saxons and the Austrians had

been sparring all morning. At

Bullenkopf the Imperial Guard and the Saxons came forward to be met by the

second Prussian division in close fighting amongst the villages and woods

where both sides gave as good as they got. The

French positioned “The Emperor’s beautiful daughters”, the 12 pounders

of the Guard Artillery, on the open hill to the left to dominate a swath of

the battlefield. The gunners

amused themselves by demolishing any enemy batteries that deployed in range

and flattening some of the Prussian occupied buildings. But

although the 12 pounders’ firepower was dangerous their major effect was

to create a vacuum swept by fire to the left of the Prussians that extended

all of the way to the Allied right where the Saxons and the Austrians had

been sparring all morning.

It

was into this vacuum that, at just before

noon

, came the best cavalry in

Europe

: the Saxon light horse leading with their heavies

behind, supported by dense columns of infantry. With

the Guard Artillery masked at last the Allies threw forward their only

cavalry in the area, a rather mediocre Prussian brigade, to stall for time.

A regiment each of Saxon and Prussian light horse met in a swirling melee of

men, horses and German expletives. The

Prussians had numbers the Saxons had élan. The

whole battlefield seemed to hold its breath as the light horsemen fought

each other to the finish and, at the very last moment, God sided with the

big battalions. The Saxon

brigadier went down wounded and the Prussians were left very battered but

still holding their ground. With

two larger and better brigades the Saxons could easily shrug off the loss of

one regiment but, as the Emperor often said, you can replace men, you can

recover ground, but you can never regain lost time. As

the cavalry were fighting it out the Austrians and Prussians had been able

to realign their forces in the centre and their right, bringing up infantry

and artillery, including the heavies from the Grenadier division. Their

job done the Prussian cavalry withdrew behind this new line. With

cannon and foot in good defensive positions to the front and either side it

was clear that the Saxon cavalry would not break through. For

a while there was a disaster in the offing as the horsemen faced artillery

fire from three directions at once, but the Allied gunners were off their

aim and the Saxons successfully withdrew.

Meanwhile

on the French right the Prussians were using their numbers to good advantage

against the Poles holding the wooded heights. Their

first effort was a crude attempt to clear the hill by brute force as the

Landwehr regiment sent a battalion forward in column against the Poles in

line. However the Poles were not

to be intimidated by Prussians. The

line stood firm and rolling volleys stopped the column dead and then sent it

reeling back into the woods. After

this setback the Prussians adopted a more scientific approach and summonsed

up an Austrian cuirassier regiment and a horse battery to set about

destroying the Polish infantry. With

three brigades plus cavalry support against two, it was a simple matter for

the cuirassiers to force the Poles into squares which the artillery and

infantry would then demolish. Whilst

this was going on the Austrian Grenadiers were brought into the central

valley to take out the French centre and the final two brigades of Austrian

reserves were brought on behind Bullenkopf.

All

in all things were not looking too good for the Emperor but he had been in

this position before more than once and he didn’t give in to his fears. On

his right he closed up the overextended French division to cover the valley

and support the left of the Poles, who were still standing, reeling and

jabbing like punch-drunk boxers. The

least battered dragoon brigade was pulled out of reserve to prop up the

Poles’ right. The struggle to

oust the Austrian division from the wooded heights above Bullenkopf was

taken over by the Imperial Guard where discipline, experience, firepower and

exterior lines were beginning to tell. In

the woods the two brigades of the Austrian division had become inextricably

mixed with their lines so closely packed that French artillery shots would

scythe through several Austrian units. On

the French left the Saxons had been surprised when the Allies had not

followed up their withdrawal. But

taking advantage of this Napoleon now sent all his aides de camp to the left

to summons up the French Reserve heavy cavalry and their Saxon colleagues to

begin a long march to the French right and centre respectively. By

2PM

the battle was set for its climax. All

in all things were not looking too good for the Emperor but he had been in

this position before more than once and he didn’t give in to his fears. On

his right he closed up the overextended French division to cover the valley

and support the left of the Poles, who were still standing, reeling and

jabbing like punch-drunk boxers. The

least battered dragoon brigade was pulled out of reserve to prop up the

Poles’ right. The struggle to

oust the Austrian division from the wooded heights above Bullenkopf was

taken over by the Imperial Guard where discipline, experience, firepower and

exterior lines were beginning to tell. In

the woods the two brigades of the Austrian division had become inextricably

mixed with their lines so closely packed that French artillery shots would

scythe through several Austrian units. On

the French left the Saxons had been surprised when the Allies had not

followed up their withdrawal. But

taking advantage of this Napoleon now sent all his aides de camp to the left

to summons up the French Reserve heavy cavalry and their Saxon colleagues to

begin a long march to the French right and centre respectively. By

2PM

the battle was set for its climax.

The

Austrian attack in the central valley moved forward professionally with the

Grenadiers screened by light horse. The

French threw out infantry skirmishers to slow them down whilst the line

infantry behind formed square. An

Austrian Hussar regiment charged the presumptuous French skirmishers and

sent them racing back towards the squares. Not

fast enough however because the horseman quickly caught up with the

terrified foot and looked certain to put them to the sword. Normally

skirmishing cavalry have little to fear from the reduced firepower of a

square, but on this occasion both squares held their fire until the last

moment and then each unleashed a devastating volley that brought the Hussars

to a shocked and bloody halt. It

had been close, but the French skirmishers scrambled to safety.

For

the Austrians though this was only a minor set back as the Grenadiers came

up to the French line. The stage

was set for the Austrian skirmishing cavalry to charge the French batteries

and keep them busy whilst at the same time unmasking the Grenadier columns

which would make short work of the French infantry squares. But

it was not to be. The Grenadiers

were fresh and relatively untouched but the Austrian cavalry regiments had

been in action all morning and, despite the possibility of victory in their

grasp, they refused to go forward. The

attack stalled within 200 yards of the French line: the Allied high water

mark. The wily old Grenadier

commander looked around him. From

the French right Saxon heavy cavalry were already arriving. On

the hill above Bullenkopf the Austrian division was falling back in disorder

which meant that the French Imperial Guard would soon be behind his flank. This

was grim. He looked behind him

for reserves. There were none. What

had happened to the promising Austrian position of less than an hour ago? For

the Austrians though this was only a minor set back as the Grenadiers came

up to the French line. The stage

was set for the Austrian skirmishing cavalry to charge the French batteries

and keep them busy whilst at the same time unmasking the Grenadier columns

which would make short work of the French infantry squares. But

it was not to be. The Grenadiers

were fresh and relatively untouched but the Austrian cavalry regiments had

been in action all morning and, despite the possibility of victory in their

grasp, they refused to go forward. The

attack stalled within 200 yards of the French line: the Allied high water

mark. The wily old Grenadier

commander looked around him. From

the French right Saxon heavy cavalry were already arriving. On

the hill above Bullenkopf the Austrian division was falling back in disorder

which meant that the French Imperial Guard would soon be behind his flank. This

was grim. He looked behind him

for reserves. There were none. What

had happened to the promising Austrian position of less than an hour ago?

Had

he not been in the valley the old Grenadier would have seen the trail of

dust moving behind the French centre and would have drawn the right

conclusions. Riding Hell for

leather the French heavy cavalry was moving completely across the

battlefield from the extreme left to the extreme right. The

three mile march took 40 minutes, hastened as it was by Napoleon in person. With

relief on the way the Poles renewed the fight and their last remaining

brigade entered the fray, catching a Prussian regiment in a defile between

the stream and the wooded heights. On

the heights themselves the other Prussian line regiment and the Landwehr

regiment were running out of steam. They

could hold the heights and the woods but not force the thinly held Polish

line on the stream below them. With

both the Poles and the Prussians near the end of their tethers only a slight

increase in force on either side could tip the balance. The

Prussians desperately rushed their cavalry brigade, still battered from its

clash with the Saxons beyond Bullenkopf to support their infantry. At

the same time the commander of the Austrian reserves, an infantry brigade

and a hussar brigade, did not wait for Charles’ instructions and moved on

his own initiative to backstop the Prussians and secure the Allied flank.

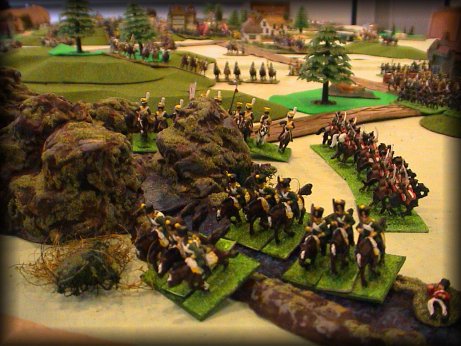

A

sort of hush descended on the battlefield as the Austrians and Prussians on

the heights saw the dust cloud thrown up by 3500 horses move up on the

French right. Two heavy brigades

deployed in depth, with regiments of carabiniers and cuirassiers leading,

supported by another brigade of dragoons to protect their flank, thrust

across the stream. Nothing

daunted the Austrian and Prussian light horse descended from the heights to

meet them. The Allies were more

numerous than the two leading French regiments but were completely

outclassed. The Allied cavalry

was bloodily repulsed but at least they had halted the French vanguard. The

French second line of cuirassier regiments would come up soon but by then

the Austrian infantry and the Allied artillery would be firmly ensconced in

the woods and on the heights so that even the best cavalry would not break

through.

And

there, effectively, the battle ended. As

the heat of the Saxon afternoon bore down, men and horses who had been

fighting since dawn could give no more.

The intervention of the Cavalry Reserve had saved the French right

and pulled off the Allied reserves that could have made the Austrian

Grenadier attack in the central valley decisive.

The corps of Polish and French infantry had been wreaked, but in

return the Prussian line division had been badly battered and the Austrian

division in the woods above Bullenkopf was in dire straits as the Imperial

Guard closed in for the kill. In

this situation withdrawing the Grenadiers from the valley would be

difficult, but not impossible. Although

the Austrian cavalry there had little offensive punch left they could still

cover a rearguard competently. The

Austrians still had two large divisions untouched, one of which even

included a fresh dragoon brigade, but these were now stretched literally

right across the battlefield. Spread

out like this they could hold out in advantageous terrain indefinitely but

they had little offensive value. The

Saxons had handled themselves well and were still largely untouched. Some

units had been knocked about but both the Saxon divisions were still

functioning. And

there, effectively, the battle ended. As

the heat of the Saxon afternoon bore down, men and horses who had been

fighting since dawn could give no more.

The intervention of the Cavalry Reserve had saved the French right

and pulled off the Allied reserves that could have made the Austrian

Grenadier attack in the central valley decisive.

The corps of Polish and French infantry had been wreaked, but in

return the Prussian line division had been badly battered and the Austrian

division in the woods above Bullenkopf was in dire straits as the Imperial

Guard closed in for the kill. In

this situation withdrawing the Grenadiers from the valley would be

difficult, but not impossible. Although

the Austrian cavalry there had little offensive punch left they could still

cover a rearguard competently. The

Austrians still had two large divisions untouched, one of which even

included a fresh dragoon brigade, but these were now stretched literally

right across the battlefield. Spread

out like this they could hold out in advantageous terrain indefinitely but

they had little offensive value. The

Saxons had handled themselves well and were still largely untouched. Some

units had been knocked about but both the Saxon divisions were still

functioning.

And

thus it was that Archduke Charles found himself pulling back before Napoleon

again. In 1809 he had run the

Emperor very close but had been defeated in the end. In

1813 what the soldiers came to call “the slaughter of Bullenkopf”, where

70,000 men fought by accident and achieved no decisive result, had shown was

that the days when the French could hold the rest of

Europe

in contempt had passed. Soon

it would be Germans: Austrians, Prussians, maybe even Saxons who would stand

on the blood soaked field as the French withdrew.

“Saxons”,

thought Charles, “ Saxons… Yes maybe I should get in touch with those

chaps. They should be able to

see the writing on the wall as well as anyone.”

The Game

The

game was set up on a Friday night and played out over the Saturday and

Sunday in Ngau Tau Kok: hence “Bullenkopf”. The

sides were exactly equal in points at 720.5 each. Over

1400 figures were used. The French had quality the Allies quantity, 34,000

men against 42,000, a total of 292 hits against 317. The

table was 12 foot by six foot.

Jeff

was the Emperor, aided by

Adrian

(pun intended) leading the Saxons. The

Poles were handled by Andrzej (naturally) on the first day and Dick on the

second. Neil was the Archduke,

Dieter controlled the Prussians, (and he is bonkers enough to make a

credible Blucher,) whilst James commanded two of the Austrian infantry

divisions. The wily old

Grenadier was yours truly.

The

set up was kriegspieled by using an abstract system to represent the

approaches to the battlefield through which the two commanders deployed

their brigades. This was great

fun for me as the umpire as Jeff and Neil tried feint and counter-feint to

seize vital bits of ground and bamboozle each other. But

they largely succeeded in confusing themselves. If

I did this again I would have them deploy by division, not brigade. It

would be quicker, neater and more historical. However

the system worked well, both commanders liked it and we ended up with a

deployment that was a far cry from the normal “12 inches in” line ups

that we so often see. It also

meant that the troops were deployed in their fighting positions so that when

the rest of the guys arrived on Saturday they were straight into combat …

no time consuming approach marches.

Once

the game got going we averaged one move every 45minutes of play. Not

too bad considering the amount of lead that had to be humped about the

battlefield. Another player on

each side to move toys and make decisions might have speeded things up a bit

but then again the tendency for multiplayer games to degenerate into agonies

of indecision and endless discussion might have been exacerbated.

Jeff

did his best to role-play the Emperor with his powers declining. He

blamed his allies for his setbacks: “I

gave him nine pips and he didn’t support me!” Maintained

the myth of his own infallibility: “I was not hoodwinked!” And was

suitably imperious to both subordinates and opponents alike. Andrzej

for one will not take tactical advice from him again. James

and Adrian maintained a gentlemanly professionalism throughout the

proceedings. Dieter drove Neil

to distraction but such are the perils of coalition warfare. However,

my vote for “man of the match” goes to Dick who was dealt a very weak

hand when he took over his command on the Sunday but played it with

consummate skill. I of course

helped him a bit when I put the pox on the Austrian offensive by saying,

with only a hint of pity, “Well the only thing that will save those light

infantry is two sixes from those squares.” But the look on his face when

the dice obliged made the whole game worthwhile!

Given

the completely equal points values and command this game was always likely

to end in some kind of draw but I must admit I was surprised, and very

pleased, at the shifts and changes that took place. With

attacks, counterattacks, withdrawals and realignments there was a dynamic

and fluid quality about the game that seemed very Napoleonic. For

most of the game it seemed that the allies had the upper hand but their

command and control problems prevented them from exploiting the advantages

that came their way. The French

on the other hand kept their corps together. Therefore

they were better able to recover quickly from setbacks and take advantage of

the opportunities that came up. Thus

what looked like being a winning draw for the Allies ended up as a winning

draw for the French. In a moment

of unbecoming humility the Emperor summed up The Slaughter of Bullenkopf as:

“Not so much a tale of a battle won. More a tale of a battle lost.”

Finally,

a very, very big thank you goes to Jeff and Amy for their superb

hospitality. Alfresco champagne

lunches should be a feature of all wargames and Jeff’s efforts in feeding

and watering the combatants over the weekend were unstinting. Although

for some reason Bullenkopf never got into the history books, for the

participants the catering alone will make it a battle to remember!

back

to napoleonic wars

|