|

EDWARD,

ARTHUR AND PETER

A

trip to the "Ting Yuen" and the

Pre-Dreadnought

Battlefields of the Yellow Sea

by

Peter

Hunt

|

|

The ensign of the

Imperial Chinese Navy flies over its newest battleship. |

These

days you do not get many chances to tread the decks of a brand new

pre-dreadnought battleship. Especially

one that was sunk 110 years ago. Chances

to see mighty Krupp guns standing guard over craggy cliffs defending naval

bases, just as they did in 1890, are almost as scarce.

But you do not need a time machine to do these things, just tickets

to Wei Hai (formerly Port Edward), and to Lushan (formerly

Port Arthur), which are situated on opposite sides of the Yellow Sea in

North China

.

There

are a few preserved pre-dreadnoughts and ironclads out there but not many.

So the good people of Wei Hai’s idea of building a 1:1 scale

replica of the Ting Yuen, the flagship of the Chinese Beiyang, or Northern,

Fleet during the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, struck me as a feat of

imagination that was well worth supporting with my tourist dollar.

All the more so since the trip can easily be combined with visits to

the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese battle sites at Wei Hai and Lushan.

Getting

There

Wei

Hai can be reached by air or train from

Beijing; or by car from Jinan

(six hours) or Qingdao

(three hours) both of which have flights from

Hong Kong. Lushan is less than an

hour’s drive from Dalien which has good international and internal flight

connections. There is also a

ferry between Wei Hai and Dalien.

|

|

|

The western entrance to

Wei Hai Wei ~ Liu Kung Dao as seen from the He Qian Hotel |

In

Wei Hai I commend the He Qian Hotel to you.

It has nice rooms, good food and excellent service, but, for the

pre-dreadnought buff, its location, at the end of the promontory that makes

up the land side of the deep water entrance to the bay, right on top of what

used to be the base’s main defence fort is another key selling point.

Nothing today remains of the six 24 cm and two 21 cm Krupps guns that

were here, except for the grassed terraces on which they stood, but the

views are fantastic. Dalien has

lots of nice hotels. We stayed

in the Swissotel which has good views of the harbour that you can pour over

with your maps of 1904.

A Bit of Background

The

hero of this piece is Admiral Ting Ju-chang, the commander of the Beiyang

fleet. He was not a great Admiral, but then, since he was a cavalry officer

this is understandable. He was, however, brave, honest, loyal and

dependable. In short he was a gentleman. It is China’s tragedy that he had to take his orders from, the villain of this piece,

the Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi. After

China’s humiliation in the Second Opium War a Sea Defence Fund had been

instituted, using customs revenues to build a modern battlefleet.

The Ting Yuen and her sister represent the best use of this fund.

By

the end of the 1880s

China

had the largest, best equipped, and one of the best trained fleets in

Asia. Unfortunately during the 1890s Tz’u-hsi dipped into the fund for her own

personal use, most notably to rebuild the

Summer

Palace, to include a concrete paddle steamer. Estimates of her peculation vary,

but it was in the range of 10 to 21 million Taels, enough to buy three to

seven of the best battleships in the world. Unfortunately the Ting Yuens

were the first, and only, battleships that China

bought. By that time that war came with Japan

in 1894 the Empress Dowager had a very nice palace, but her battlefleet was

short on pay, ammunition and sea-time. To make matters worse Tz’u-hsi

exhibited the same sort of strategic direction in the Sino-Japanese War that

she did in the later, equally disastrous Boxer Rebellion. Completely out of

touch in the Forbidden City, and basing her judgement on information from ill-informed and self-serving

sycophants, she never appreciated the reality, nor the gravity, of the

situation she was in. As a result of this wishful thinking the hapless

Admiral Ting was given totally unrealistic “rules of engagement”.

|

|

|

The Ting Yuen today |

But

first, the ship. When I visited the Mikasa I was

struck by how Nelson might have found that ship from a hundred years after

his day very familiar in places, especially on the long, open tertiary gun

decks where the guns fired through open ports on the broadside.

Neither Nelson from 80 years before, nor a sailor from 120 years

later, would find much to be familiar with in the Ting Yuen.

This is because she is a representative of a short, narrow and soon

extinct branch of battleship evolution that is best described as the central

citadel turret (or barbette) battleship.

The design of these ships came from applying a sort of “Occam’s

Razor” methodology to the problems of dealing with the great improvements

in armour protection and gun penetration that were taking place in the late

1870s and 1880s. The thinking

went something like this:

-

Only

the very heaviest armour was useful, as anything else could be

penetrated.

-

Only

the very heaviest guns were useful, as anything lighter could not

penetrate heavy armour.

-

Because

of the weight there could not be much heavy armour, nor many heavy guns.

-

Therefore

the solution was to concentrate the vitals of the ship ~ her machinery,

magazines and guns ~ in a central citadel which could be heavily

armoured. The rest of the

ship was left unarmoured except for a protective deck at the waterline.

Whether the main guns were in armoured turrets or open barbettes

was a matter of national taste and weight.

|

|

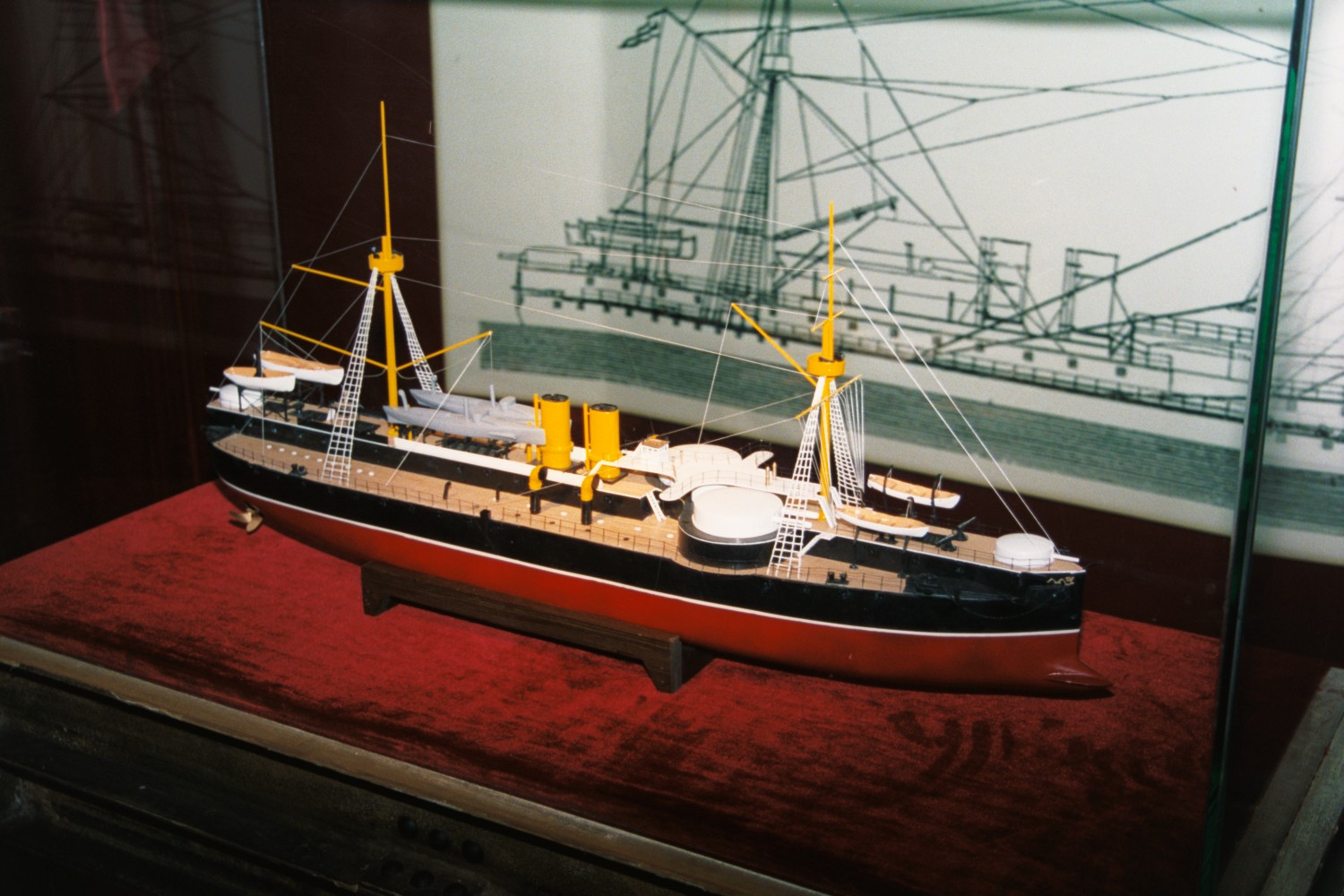

The model shows the

layout of a central citadel battleship ~ main guns and propulsion

concentrated amidships |

The

Italians were the originators of the design and built three classes for a

total of seven ships. The

British responded with three classes of five ships.

The two early American second-class battleships gave more than a

passing nod to the design theory too, and two were built for Brazil

as well. The fad for these ships

lasted from the late 1870s to the late 1880s, so when Ting Yuen and her

sister Chen Yuen were ordered in 1881 and 1882 they were considered state of

the art vessels at the cutting edge of battleship design.

Ting

Yuen and Chen Yuen were built in the Vulcan Yard at Stettin

Germany, now Szczeczin,

Poland. They displaced 7,670 tons and

their armoured citadel was covered by 14” of compound (steel over iron)

armour. They mounted four 12”

breach loading guns in a barbette amidships, with the guns on two turntables

surmounted by thin, but complete, shields that gave the impression of

turrets. Right forward and aft

were armoured turrets mounting one 5.9” gun each.

They also carried six 37 mm Hotchkiss multiple barrelled guns and

three torpedo tubes. In keeping

with the fashion of the time they also carried two second class torpedo

boats each, to provide for attack and defence, especially at night time.

They could make nearly 16 knots when new.

All-in-all they were very nearly equivalent to the later British

“Edinburgh” class which, for their time, were considered to be first

class battleships, although the Ting Yuens were rather smaller and a bit

slower with shorter calibre main guns. The

Ting Yuens were certainly better ships than their British contemporaries the

Agamemnon class which had only muzzle loading guns.

|

|

|

Ting Yuen's stern and

5.9" turret |

The

central citadel turret battleships were criticized in their day on two

counts. Firstly mounting the two

turrets in the middle of the superstructure, instead of one each end of it

in the conventional manner, severely restricted the arc of fire of the

turrets on their opposite broadsides. The

type’s supporters claimed that since both turrets could fire fore and aft

this would compensate for the lack of wide broadside arcs of fire.

Secondly it was argued that the unarmoured ends of the ships would be

vulnerable to even relatively small guns and shot to pieces in battle,

leading to fire and flooding which would result in the loss of the ships

even if the citadel remained inviolate.

Although the British “Inflexible” fought at the bombardment of Alexandria

and one of the Brazilians was involved in a civil war this was hardly a good

test for the design. However

Ting Yuen and Chen Yuen were in heated action for four hours at the Battle

of the Yalu in September 1894 so they were truly tested.

Their experience there proved the type’s critics right about the

arcs of fire, but wrong about the vulnerable ends.

At

the Yalu the Ting Yuen’s very first shot, fired almost straight ahead,

missed the enemy. But the blast from the gun demolished the flying bridge

upon which Admiral Ting and his British advisor, W. F. Tyler, were standing,

knocking the admiral out for two hours and deafening Tyler

for life . . . obviously the useful arc of fire of the guns was limited!

|

|

|

12" barbette and

the (literally) flying bridge above |

On

the other hand the Ting Yuen was hit 200 times during the battle and Chen

Yuen 150 times, but, although their superstructures were peppered, their

citadels were not penetrated. And whilst they were badly knocked about, they

were not endangered. The Chen

Yuen was shipping some water but the main reason for Admiral Ting’s

withdrawal was because his ships had used up most of their ammunition.

Since it is the aim of a battleship to dish out punishment, rather

than take it, then the design can be considered a success if the ships

survived to dish out all the punishment that their ammunition supply

allowed.

Sadly

for Ting and his sailors the punishment that they dished out was much

reduced because of the pernicious effects of corruption in the Chinese

government and naval suppliers which resulted in much of their ammunition

being old, substandard or even filled with cement rather than bursting

charges. Consequently the Battle

of the Yalu saw five Chinese ships sunk for four Japanese ships crippled.

With better ammunition the balance could easily have swung in China’s favour.

After

repairs at Lushan, and re-ammunitioning (again with sub-standard rounds)

at Tiensien, Admiral Ting moved the Beiyang fleet to Wei Hai.

The ships still constituted a powerful enough “fleet in being” to

constrain Japanese movements. But

then the Chen Yuen ran aground and, although able to fight her guns, became

unseaworthy. Since the two

battleships constituted

China

’s main material superiority over the Japanese the crippling of Chen Yuen

swung the balance of naval power firmly in Japan’s favour.

Even

whilst the Beiyang fleet was still in being the Japanese took a major risk

and despatched an expeditionary force to Lushan.

The base fell to Japanese assault in one day.

The army under General Nogi pierced the defences whilst the Japanese

Navy’s torpedo boats broke into the harbour and supported the land troops

with their small calibre, quick firing guns.

The attack on Lushan was followed by three days of looting and rapine

by the Japanese. Oddly enough

the modern Chinese version of this atrocity stresses the resistance of the

garrison and the civilian population. This

appears to me to be a “reinterpretation” in line with the Maoist theory

of “people’s war”.

It is

clear from contemporary accounts, and the time frame, that the atrocity was

not provoked by a civilian guerrilla campaign but was a Nanjing

style excess where the Japanese army was let out of control and acted in the

most bestial manner.

After

the fall of Lushan the Japanese turned their attention to Wei Hai and

Ting’s fleet. Lushan had been

built up as the main base for the Beiyang fleet, complete with a dry dock

and workshops. Wei Hai was best

described as a protected anchorage. The

bay is protected by the island

of

Liu Kung Dao

on which was located the Beiyang fleet administrative headquarters and coal

stocks. Ten modern forts protected the island and bay from seaward, whilst

six, considerably weaker, positions secured the landward approaches.

The Japanese launched an army to take Wei Hai from the landward side

and the situation turned into a precursor of the 1942 Singapore

debacle. Wei Hai’s main

defences faced seaward and Ting found that instead of the batteries

defending his fleet his ships had to fire to defend the batteries.

When the batteries fell to Japanese attack the fleet had to maintain

the fire to prevent the captured guns being turned against them.

To

keep up the pressure the Japanese launched a series of torpedo boat attacks

into the bay. Some were thwarted

by the freezing winter weather, some by friendly fire, and some by

confusion. But, after six attacks the Ting Yuen and three other ships in the

fleet had been sunk or crippled. Chinese

counter-fire against the Japanese blockaders was hamstrung by their poor

ammunition. Just as at the Yalu,

Japanese ships were hit several times by shells that didn’t explode.

With

the Japanese army and navy tightening it’s grip the days of the Beiyang

fleet were numbered. A sortie by

the fleet’s torpedo boats was quickly mopped up by the Japanese.

Without serviceable ships and with no hope of relief, Ting accepted

the inevitable. On 12th

February 1895 the Beiyang fleet surrendered.

Some commanders turned over their ships intact in the hope of

placating the Japanese and thus averting another atrocity like Lushan.

Others were made of sterner stuff and the Ting Yuen and some other

ships were destroyed by their own crews.

The senior commanders of the Beiyang fleet were mostly honourable

men, and many of them, including Admiral Ting, committed suicide.

The

Ching dynasty was rapidly approaching its nadir.

With the Beiyang fleet destroyed China

was even more open to imperialist exploitation.

Under the peace treaty

Japan

took no territorial rights outside of

Korea

but imposed a swinging indemnity on China

and sought economic dominance. To

thwart the Japanese the Chinese leased the Kwangtung

Peninsula, with Dalien and Lushan to Russia. Acting on the pretext of

protecting missionaries the Germans seized Qingdao. The Russian and German

presence in

North China

was not welcomed by the British, who then leased Wei Hai to keep an eye on

them. The lease conditions specified that the British would leave the town

if the Russians left

Port Arthur.

British

dreams of a Hong Kong on the

Yellow Sea

were still born. The location

and economics were wrong. “Port

Edward” became a base for the British and Chinese navies, a moderately

successful Treaty Port, and a convenient place for the Hong Kong and Shanghai

expatriates to escape the heat of summer.

As if to highlight this recreational aspect, whilst Hong Kong and Singapore

both had cricket pitches in the middle of town, Port Edward went one further

with a full sized golf course as its centrepiece!

The

future of Port Arthur, as Lushan was renamed, was far less pacific.

The Chinese economic and military withdrawal from the North-East

brought

Russia

and Japan

into an almost inevitable conflict. Learning

from the Chinese experience the Russian’s strengthened the defences of Port Arthur

and installed a powerful fleet which the Japanese matched as described in my

article on the Mikasa.

The

Japanese started the 1904 war undeclared with torpedo boat attack on

Port Arthur

followed by naval bombardments. When

the decisive fleet battle did not materialize the Japanese Third Army under

General Nogi, the victor of the 1894 attack, was given the job of reducing

the town.

Whilst

Nogi was in command of both Japanese assaults on Port Arthur, the 1904-5 battle was very different to that of 10 years earlier.

The easy victory of 1894 was not repeated and the siege dragged out

over six months, in what is now regarded as a precursor of the trench

warfare and appalling casualties of World War One.

Unable to reduce the land defences the Japanese made three attempts

to block the narrow harbour entrance by sinking ships in the channel but

this was also ineffective. Eventually

the Japanese seized Hill 203, some three miles from the harbour, and from

this position they could direct 11” coast defence howitzers to drop fire

on the Russian fleet. With the

fleet destroyed and after nearly 60,000 Japanese and 31,000 Russian

casualties

Port

Arthur finally surrendered on 2nd January 1905.

The battle cost Nogi his reputation and his own son.

Only a direct order from the Emperor prevented him from committing

ritual suicide to acknowledge his responsibility.

Nogi lived on with his loss until the Emperor died and then, released

at last from his order, took his own life.

With

the Japanese in possession of

Port Arthur

and the

Korean

Peninsula, and between 1915 and 1922 Qingdao

as well, the

Yellow Sea

became a Japanese lake. Thus Port Edward, rather than being a strategic

balance for the British, became a strategic liability.

Although the lease condition was changed to allow the British to

remain until the Japanese left Port Arthur

the British knew that this was wishful thinking.

Port Edward had outlived its use as a pawn in the Imperialists’

game and in 1930 was amicably returned to China

.

Port Arthur

remained under Japanese

occupation until 1945 when the Russians re-took it and once again

established an ice-free naval base on the

Yellow Sea. As the Cyrillic graffiti on

the various Japanese monuments show, the irony of this turn of events was

not lost on the Soviet soldiers and sailors who remained there until 1954

when Lushan was finally returned to Chinese sovereignty.

The

Ting Yuen Today

The

Ting Yuen had its

“soft” opening on May Day 2005. When

I visited in mid-May the ship had a wonderful, wet paint smell, but the

landside facilities and a few things on the ship were still not finished.

Not to worry ~ in my opinion the 50 RMB, (US$6) admission was a

bargain. The ticket price gets

you an illustrated brochure, and guides (Putongwha only) in Beiyang fleet

ordinary seamen’s uniforms, to show you around and answer questions.

But if, like me, your Putongwha does not extend much further than ordering

beers, you are free to wander at will.

|

|

|

|

One of the guides and a

kotchkiss |

The

upper deck and the officers’ quarters on the main deck have been recreated

in good detail, right down to the rigging, the torpedo boats, the tertiary

armament and the cutlery in the wardroom.

I was interested to note that in addition to the as built armament

given in the standard sources she is shown with two additional 6 lber and

four more 12 lber anti-torpedo boat guns on the weather deck.

Most

of the main deck and the lower deck are given over to exhibition areas.

The former concentrating on the original ship itself and the building

of this replica, and the latter on the Beiyang fleet and the Sino-Japanese

War in general. This includes

models of all the ships on both sides and also a diorama wargames table of

the Battle

of the Yalu with the ships in about 1:300 scale (big beasts!).

This was still under construction when I visited but the ships will

float on real water when it is finished ~ neat or what?

|

|

|

The,

still dry, wargames table.

The

Chinese ships are inaccurately shown in "Victorian" livery;

in fact, they were in two-tone grey. |

One

touch that I particularly liked is that the side spaces on the museum

floors, which on the original would have been coal bunkers, have been turned

into life sized representations of the parts of the ship that could not

recreated ~ a galley, a mess deck, a magazine and a stokehold.

Further forward one of the torpedo rooms is recreated and it’s well

worth a look. I, for one, never

realized that the “fixed” torpedo tubes that you read about were

actually trainable over an arc of about 30 degrees.

There is a helpful photograph of the original installation there for

disbelievers.

|

|

|

The trainable torpedo

tube |

Overall

I was very impressed with the Ting Yuen.

Clearly a lot of attention has gone into recreating her and a very

good job has been done. The

staff are all friendly and helpful and seem to take a real pride in their

endeavour. As you wander around

her it is easy to feel you are treading in Admiral Ting’s footsteps even

though this Ting Yuen is a creation of the 21st century, not the 19th.

She is a fine experience and if, like me, you can find functional

beauty in these war machines, a fine sight.

This sight can best be savoured from some little dai pai dongs just

across the bay where you can sit with some fresh seafood and a bottle of Yan

Tai beer, and gaze on the world’s newest pre-dreadnought battleship.

|

|

|

The view from the dai

pai dongs |

go

to Part II

or

back to

other

periods or back

to expeditions

|